IMAGES: PAUL SWENBECK Google Images

CONTACT:

- (215) 435-0388

- wormwoodnhaze@gmail.com

- 1234 Leopard Street, Philadelphia, PA 19125

GALLERY: Fleisher Olman Gallery

VIDEOS:

Vimeo: http://vimeo.com/36121423

- Jeffrey Bussmann visits Paul Swenbeck in his studio to talk about recent work in the show Dor and Oranur at Fleisher/Ollman Gallery. 6 Minutes

Vimeo: http://vimeo.com/36171861

- Jeffrey Bussmann talks to Paul Swenbeck about past work from the “Mandragora” and “Starsprout” series, and new work in the show “Dor and Oranur” at Fleisher/Ollman Gallery. 7 minutes

REVIEW:

REVIEW — ART IN AMERICA

PHILADELPHIA These well-paired exhibitions of works by New York-based Joan Nelson (b. 1958) and Philadelphia-based Paul Swenbeck (b. 1967) transported the viewer to very different otherworldly environments. Nelson’s 15 small boxes offer terrariumlike landscapes for careful examination, and Swenbeck’s eerie installations of ceramic deep-sea life-forms invite an exploration of his personal mythology, which takes from the primeval as well as the fantastic.

Nelson’s pieces, all completed in 2011, merge scenes reminiscent of paintings by the Hudson River School or German Romantics with traces of Joseph Cornell’s boxes. Each object’s wood frame wraps around stacked glass panels painted with oil and acrylic, producing layered landscapes that sandwich tiny items such as glass beads and plastic netting. Untitled (#55), approx. 9 by 8 by 3 inches, features intricately painted trees before a soft blue sky; intense yellow areas suggest a fire in the woods. The atmospheric layers are interrupted by a crystal comet shooting between the clouds, trees and rocks. Nelson’s technique of stratification gives the space a distinctive density. This is especially true of Untitled (#48), in which branches dangle in front of clotted red filaments on the right and a hazy turquoise sky at the top. The whole scene seems to be in an aqueous suspension. Illuminated from the back, Nelson’s microcosms exude gently glowing hues: warm oranges, bright pinks and ominous purples. But to discern the details, the viewer needs to get close and peer inside, bringing to mind Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés, housed at the nearby Philadelphia Museum of Art.

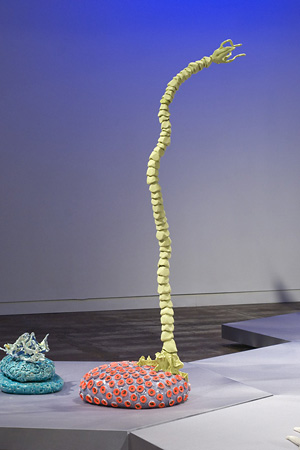

Swenbeck’s approximately 20 ceramic sculptures (all but one 2011) were divided into two installations. A large gallery was filled with clusters of richly textured forms confronting each other on a fictional sea floor, made up of contiguous low platforms covered in silvery spandex. One grouping—including two works from the “Crinoid” series and one from the “Porifera” (sponge) series—exemplified how the artist balances chromatic energy. (A crinoid is a type of marine animal that has existed since the Paleozoic period.) The largest element was a piercing cobalt blue crinoid that, at 38 by 17 by 8 inches, has a vase-shaped body with a long armlike tentacle reaching upward with an odd aggression. It was held in check by a sea sponge and a less threatening crinoid, both in yellow and orange. Throughout, the extended limbs and artificial colors suggested a cartoon esthetic, adding a playful curiosity to the potentially ominous organisms.

On the floor, walls and ceiling of an adjacent alcove, six additional sculptures created a denlike space with ritualistic undertones. Subtly shaped clay objects, which preserve the contours of the artist’s hand, hovered on the walls like anamorphic skulls. Cat and bird creatures, respectively titled Thinking with the Blood and The Sacrifice, hint at imminent danger. Terminal Buzz, a collaborative sound piece done with Aaron Igler that transforms animals’ echolocations, permeated the exhibition and became its relentless heartbeat. Swenbeck’s new works push his longtime interests in pro- ductive new directions, wedding marine biology and science fiction.

REVIEW

at Fleisher/Ollman Gallery through February 18 by Jeffrey Bussmann

At the opening reception for Paul Swenbeck’s Dor and Oranur I was immediately drawn to the two hanging wire-form pieces in the show. Swenbeck invited me into his studio for a demonstration of how he makes them, which he sees as the potential beginning of a new body of work. He joked that making a video was akin to producing a cooking show. After some reflection, I found the comparison apt. There are currents of magic and witchcraft that run through Swenbeck’s work; he let me into his process, part chemistry and part conjuration.

I also spoke with Swenbeck about his previous Mandragora and Starsprout series, and how they relate to the current show. The element of the supernatural still holds sway in Dor and Oranur, but he has delved deeply into a delectable triad of paleontology, psychoanalysis, and science fiction.

Jeffrey Bussmann works at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania. He is currently researching Brazilian cultural organizations for his master’s thesis in Arts Administration at Drexel University. He also writes for his blog Post-Nonprofalyptic.

REVIEW

Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957) was an Austrian-American psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who started out his academic career respected (working with the likes of Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein) and ended his career as a mad-scientist type whose work was destroyed by the FDA.

Reich believed he discovered a primordial cosmic energy that he named “orgone”. The machines he built to harness orgone were called orgone energy accumulators and they had the appearance of a large, hollow capacitor. A patient, in need of healing, would sit inside an orgone energy accumulator. Sitting inside an orgone-making box would supposedly bring about health benefits of one kind or another. Press at the time seemed to think orgone accumulators were somehow sex machines that caused permanent erections and orgone energy was in fact a harnessed orgasm.

Reich bought land, 160 acres in Maine, that he christened “Orgonon”. On this land he built two laboratories dedicated to the study of orgone. One experiment conducted on Orgonon land was called “The Oranur Experiment”, which stood for ORgonomic Anti-NUclearRadiation. During this experiment Reich discovered that nuclear radiation “antagonized” orgone energy and turned it into Deadly ORgone or DOR. Dor apparently, is a really nasty energy that does horrible things to living organisms, even worse things then what a living organism could expect from “normal” radiation sickness.

It goes without saying that the current consensus of the scientific community is that orgone theory is a pseudoscience. Evidently you can purchase orgone equipment online: here, here,here and here.

The Wagner Free Institute of Science Fiction

The world created for “Dor and Oranur” is completely encompassing. It reads less like a commercial art gallery filled with sculpture and more like a hybrid of The Wagner Free Institute of Science, The Milstein Hall of Ocean Life at the American Museum of Natural History, and what remains of the history of an ancient race still on view in the crumbling ruins of a museum set in a post-apocalyptic planet’s future. Much of this mood is accomplished through the use of lighting and sound, the gallery is lit by a combination of cool colored lights and the audible space is filled with a noise-alien-horror-movie sound track created by Paul Swenbeck in collaboration with Aaron Igler.

The sculpture itself reads as fossil or representation of actual organism, either earthly and from the depths of the ocean, or alien. Clues are dropped in the form of sculpture titles, revealing a mash-up of inspiration ranging from witchcraft, Wicca hippies, cultists, black metal, fantasy, pseudoscience, actual science, and science fiction. The tall, plant-like, “Silurian Sentinel” might reference a race of reptile-like humanoids from Dr. Who or a geologic period that ended some 443.7 Million years ago, give or take 1.5 million years. The small pokemon-looking “Wiwaxia” looks exactly as the fossil-record of the soft-bodied, scale-covered animals might indicate. Two pieces entitled “Dolmen” do not resemble the actual portal tombs or graves from the Neolithic period, though they seem rock-like and tied to a ritual use of unknown origin. Several small fossil-looking sculptures entitled “Familiars” which anyone who has read “Harry Potter” knows is an animal that hangs out with a witch or wizard, also send a mixed magical and biological signal.

It is tempting to wrap “Dor and Oranur” up in a neat little package labeled; “Institutional Critique, the kind that makes us question the origins of what’s in museums, that’s a bit Mark Dion and more Marcel Broodthaers, ‘Department of Eagles’ “. The specter of Wilhelm Reich’s biography hangs over this label, the fact that orgone was at one time considered an actual discovery, or the fact that his books were burned by the FDA, begs many questions. Who controls history? What do we believe now that is actually false? Why is some knowledge valued over other knowledge?

That heavy label might remove a lot of the pleasure of looking, and the feeling that the artist got a great deal of joy out of the making. Everything in “Dor and Oranur” is superbly crafted, made of a variety of materials, but mostly ceramics. The finish ranges from matte primaries, what could be florescent paint, and actual glazes in cerulean and more intricate secondary colors. The larger sculptures, composed of several pieces, might be held together by brightly primary sculpy or something else that resembles play dough. It is hard not to think of Tim Burton films, where dark themes and creepy critters are often cartoon-ish and colorful, made family friendly– as long as you don’t think about them for too long.

One Review a Month also reviewed the work of Paul Swenbeck in April, 2010.