IMAGES: LAURENT CRASTE Google Images

WEBSITE: LAURENT CRASTE (Gallerie SAS)

VIDEOS:

- Ton souffle qui passe – 2010 Installation vidéo http://vimeo.com/12472874

- Memento – 2010 Installation vidéo http://vimeo.com/12473025

- Les vases communicants – 2008 Centre d’exposition CIRCA – Montréal. Installation vidéo http://vimeo.com/12471992

BIO/CV:

- EDUCATION

- 2005-2007 Master in Fine Arts from the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) with first class honours.

- 1996-1997 Professional degree in ceramics. Centre de Céramique Bonsecours – Montreal, Quebec.

- 1991-1993 Master in Physiology and Anatomy, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec.

- 1987-1991 Degree in Veterinary Medicine. École Nationale Vétérinaire de Maisons-Alfort – France.

Born and raised in France, Laurent Craste has been living and working in Montreal for the past 18 years. His career has involved both a studio practice in contemporary ceramics and the teaching of ceramics at college level.

In 2003, Laurent Craste received the prestigious Winifred Shantz Award for Ceramists, awarded by the Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery. He is a regular exhibitor at Chicago’s Sculpture Objects and Functional Art (SOFA) show and has also participated in the Biennale Nationale du Canada and the Biennale Internationale de Châteauroux in France. In 2005, he was a finalist in the Carouge international competition in Switzerland. In 2007, Laurent completed a master’s degree in Fine and Media Arts; his research works have earned him a graduate award of excellence from UQAM, as well as a grant from the Centre interuniversitaire en arts médiatiques (CIAM). In 2009, he took part in the Cheongju International Craft Biennale in Korea as well as SOFA Chicago. In March 2010, he will present at PULSE, NY.

Artist Statement: “ At the heart of my artistic pursuit is the decorative object. My research centers on conceptual explorations of the multiple layers of meaning of decorative collectibles, in their sociological and historical dimensions, and also in their ideological and aesthetics ones. This approach takes its form in the re-appropriation of historical ceramic archetypes. My research considers the object as a social indicator, a “sign bearer” 1. considered as fluctuations of instruments of political power, ideological vehicles, demonstrations of ostentatious luxury and economic power, or as incarnations of emotions and experiences, the historical archetypes of decorative arts consummately provide me with useful material. Therefore, I regard the inventory of original models from the main 18th and 19th century European porcelain manufacturers and use these models as a basis for research on the status of the collectibles, by subjecting them to a practice of deconstruction and violent alternation of their formal structures, and by contaminating their traditional decorations through a subversive process of subject substitution.

Via this approach, I have recently turned my attention to an interdisciplinary practice that combines decorative objects and video in a totally original way, using ceramic models as screens for video projections.

This corruptions, formal and iconographic, as they reassess the historical, social, political and aesthetic values of the decorative object, also reveal an intense and ambiguous relationship with it.”

Translation/ Adaptation: Peggy Niloff

REVIEW

The work of Laurent Craste lies at the crossroads of two mediums, participating in the world of visual arts, but never stepping beyond its borders. Ceramics, linked by tradition to crafts, requires a technical knowledge and know-how so restrictive that artists are prompted to remain within canonical forms, never pushing their limits. Video art, the recent avatar of the moving image, does not always acknowledge its main ancestor, cinema. The innovative aspect of this work is the combination of the two mediums with the addition of humorous or dramatic short stories, encompassing an autobiographical element that never descends to self-righteousness. The digital animation embues the stills with life and enables the self-portraits to take shape and meaning over time, at the very centre of the video, as opposed to the immediacy of reception provided by the ceramic form. The video becomes the critical analyst of ceramics as a medium, revitalizing it and making it a theoretical object. Craste’s plan is to be neither heavy nor impenetrable: the humor that runs through his work saves it from this fate.

In terms of narrative content, the criticism of decorative art is filtered through the stills underlying Craste’s recent works. The outmoded ideas disseminated by bucolic scenes, floral bouquets and exotic trash, are presented and staged to highlight their racist or sexist elements and the conservatism of the object’s owners. Therefore the critique of the representation also becomes a critique of the medium.

Pascale Beaudet – Translation / adaptation: Peggy Niloff

The silences of still life: Laurent Craste.

UNUSUAL APPOSITIONS GOVERN THE RECENT WORK of Laurent Craste. Ceramics serves as both physical support and signifying material in his video and much of the short sequences that make up his recent production–including a public presentation in 2009, an exhibition in 2008 and three previous ones in 2007 (1)–are characterized by the self-mocking displays of a body put through its paces.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Decorative objects played a crucial role in Les Vases Communicants, his most recent gallery exhibition. Reconstructed in the small exhibition hall was part of a well-to-do living or office space. Two porcelain copies of Sevres vases stood on an Empire style secretary; above it, a white faience dish hung on a background of red wallpaper whose vine tendril motifs acted as a foil. Projected onto the potbellied midsection of the vases, following the conventional pairing of decorative objects, were two video streams showing two similar though not identical representations of the artist. Projections on the dish also drew on traditional decorative themes. To gain access to these screenings, however, one had to wade through the flip side of the decor, a space crammed with wires and plugs.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Though very close to the Sevres originals, the vases were inspired by traditional models rather than directly copied from them. Imitating their general structure, Craste throws the pots himself, placing great importance on construction and on this particular technique, both for the sensuality of the materials and for his own representation in the video work, in which he figures as the main character. While likenesses may vary, both the vases and the video are self-portraits.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Thus, the artist features nude in his one-man show. In a first video sequence, he appears in a mock-classical and increasingly ridiculous pose; in the following one, he gives way to paroxysms of anger, in the last, he labours in the cold. Viewers are presented a nearly 40-year-old body, with its attendant signs of excess weight and incipient baldness. Unforgiving in the presentation of his physical accoutrements, the artist piles still more hardship onto his body.

The installation would seem to be a videographic reformulation of still life, itself a discourse on the ephemeral nature of objects and beings. Still life, however, is here deflected through its use in the decorative arts, especially porcelain painting. Concurrent with the projections on the vases, where the neoclassical and statuesque poses become increasingly untenable, another subject is dealt with on the plate: an animated still life, in typical decorative ceramics style, where flowers wilt and petals drop one by one. While, in the second ‘tableau’, the artist screams himself hoarse (though we can’t hear him) and the image grinds to a numbingly slow pace, the plate presents us with two fat round pears that are gradually covered over by big flies. And during the third sequence, where we see the artist digging the frozen earth with pick and shovel and where the tension created by opposing tones of self-mockery and the dramatic neutralizes extreme emotion, on the plate, a country house with a two-gabled metal roof gradually fades as an intense light saturates the scene. In the three videos, spectators are exposed to emotions of changing intensity–melancholy, anger, then sadness–that keep and hold one’s attention.

The presence of the house as a third sequence breaks with the content of the other two; one might have expected a variation on the theme of decomposition (hanging aged meat, for instance). Instead, we have this house that disappears. In the decorative sphere, peasants and shepherd maids often figure prominently, along with country houses. Since the body is the main concern here, the artist chose to replace it, metaphorically, with this dwelling. The house, in psychological terms, is also childhood, a regression to an often idyllic experience (or construction), just as the decorative cliche is a nostalgia for better times, an improbable golden age.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Still life, considered a minor genre in the beginning (the 16th century), is still relevant today, whether in painting or in other media. In Barbara Bloom’s Half-Full, Half-Empty, for instance, recently put online by the Dia Art Foundation, we see a typical still life tabletop, but in contemporary style, with objects appearing and disappearing to the accompaniment of an off-screen voice. Many other artists might be included in this old but on-going tradition–one thinks of Tony Cragg, Christian Boltanski, Ilya Kabakov.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Craste used the porcelain dish projection technique for a presentation during the All-Nighter at the Montreal High Lights Festival, on 28 February, 2009. With himself on display once again, set in profile, his face is gradually covered by flowers that form the plate decoration; a troublesome fly then begins to annoy him, until he shakes it off and, in so doing, throws all the flowers back where they came from. The flowers could have formed a crown, had the artist braided himself one but he preferred to continue in his amusing vein.

A ceramist by training, Craste was first influenced by the forms of Grecian vases, which he personalized by equipping them with organic fragments, male or female genitals, sometimes arranged into secular altars. He now draws on the traditional repertoire of the decorative arts, like bouquet of flowers or the garlands surrounding medallions. In the sphere of still life, paintings of flowers derive from scenes of the Annunciation and, therefore, have a female connotation. Hence the sense of incongruity elicited by the juxtaposition of the flowered frame, evoking tenderness and happiness, with the scene of male anger and frustration.

In France, still life developed into the vanitas of the 17th century, with variations on the books and human skull that were taken from paintings of saints’ cells, especially Saint Jerome’s. One may consider the scenes where Craste strikes at the earth a vanitas in motion, indicating an act of mourning.

The particularity of Craste’s approach lies in his juxtaposition of objects that are considered decorative–objects which, according a formalist rearticulation of the hierarchy of genres, are deemed inartistic–usually relegated to passing contemplation and the moving image. The crux of the matter is the supporting medium. Vases and plates are substitutes for the screen but, contrary to the latter which is meant to be forgotten, their imposing presence plays a dual role, as contemplation shifts toward a critique of the object as indicative of social status and visual stereotypes.

On the other hand, Craste’s renditions of Sevres vases and the porcelain plate are stripped of their characteristic ornamentation. They are unfinished, yet still partake in the conventional decor of an upper-class living space. The video images, then, with their expression of intense emotions or unpleasant realities, create the required divergence for the emergence of a social critique. In the purported context, the very fact of the artist’s nudity is itself an incongruity.

Another marked characteristic of his videos is their strict silence. The character’s silence helps temper the dramatic potency of some scenes but it also creates a malaise. While other artists fragment the body (like Oursler, with his detached heads or dis-embodied eyes, or Annette Messager, who collects parts of male and female bodies), here Craste stifles hearing–one of the most essential senses for film and video. A distancing is created and reinforced by the prettiness of the garland or the strip of geometric Grecian motifs.

In the installations that marked the end of his masters degree, Craste ‘sponged’ off the collections of the institutions that had welcomed him, a critical gesture, of which one of the first examples was Histoires de musees, an exhibition that took place in 1989 at the Musee d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, which brought together around 20 artists who proceeded to invest every nook and cranny of the museum. At Montreal’s Ecomusee du Fier Monde, which presented an exhibition on sports, three videos occupied one of the bull’s-eye windows; here, in Les Dievx dv Stade, Craste awkwardly imitated the motions of Olympic athletes. In the collection of religious art at the Musee des maitres et artisans, a large decorative plate emblazoned with the arms of the pope served as a projection screen for a series of identical vignettes featuring the artist with his arms crossed and in often badly held poses, sometimes making somewhat improper gestures. At the Musee du Chateau Dufresne, in the Turkish salon, Sevres vases with elephant’s-head handles served to screen a video titled J’aurais voulu etre une Mauresque, in which the artist performed a weird striptease on the theme of the dance of the seven veils.

These three installations, strongly imbued with the artist’s biography, adopted an ironic and mischievous tone while maintaining a critical perspective. Discrete, though not hidden, they commented either on the current exhibition, on its context or on ideologies embodied in or trafficked through objects within it, while his critique is conveyed through intentionally awkward role-playing of multiple identities. After the worlds of sports, Roman Catholicism and colonialism, Craste turns to the decorative arts for his critical investigations. In Les Vases Communicants, he no longer plays characters; instead, he confronts himself. After having produced socially critical works and constructed a body-mask, at once strong and fragile, like clay hardened through fire, he now turns his gaze onto himself, peers into darker areas and attempts to ‘repair’ his wounds, his mourning and exile.

FOOTNOTE

(1.) The public presentation took place during the All-Nighter at the Montreal High Lights Festival on 28 February, 2009. The most recent gallery exhibition was seen at Circa, in Montreal, from 10 May to 7 June, 2008. The three previous ones, also in Montreal, were held at the Ecomusee du Fier Monde 17-20 May, 2007 at the Musee des maitres et artisans du Quebec, 23-27 May, 2007 and at the Musee du Chateau Dufresne, 31 May to 3 June, 2007 (part of the requirement for the masters in visual and media arts at UQAM).

The work of Laurent Craste lies at the crossroads of two mediums, participating in the world of visual arts, but never stepping beyond its borders. Ceramics, linked by tradition to crafts, requires a technical knowledge and know-how so restrictive that artists are prompted to remain within canonical forms, never pushing their limits. Video art, the recent avatar of the moving image, does not always acknowledge its main ancestor, cinema. The innovative aspect of this work is the combination of the two mediums with the addition of humorous or dramatic short stories, encompassing an autobiographical element that never descends to self-righteousness. The digital animation imbues the stills with life and enables the self-portraits to take shape and meaning over time, at the very centre of the video, as opposed to the immediacy of reception provided by the ceramic form. The video becomes the critical analyst of ceramics as amedium, revitalizing it and making it a theoretical object. Craste’s plan is to neither heavy nor impenetrable: the humor that runs through his work saves it from this fate.

In terms of narrative content, the criticism of decorative art is filtered through the stills underlying Craste’s recent works. The outmoded ideas disseminated by bucolic scenes, floral bouquets and exotic trash, are presented and staged to highlight their racist or sexist elements and the conservatism of the object’s owners. Therefore the critique of the representation also becomes a critique of the medium.

Holding a doctorate in art history from the ‘Université de Remnes 2 (France), Pascale Beatudet is an independent curator, writer and lecturer.

As an organizer, Pascale Beaudet has designed and coordinated twenty contemporary art exhibition. In 2009, she curated two biennials: The Fondation Derouin outdoor sculpture Symposium in Val-David, and the Biennale internationale de lin à Portneuf (visual arts component). In conjunction with Montreal, City of Glass, slated to begin in april 2010, the Musée de Lachine has requested that she design an exhibition entitled Lignes. She has also authored hundreds of articles on modern and contemporary art, thirty of which have been published in exhibition catalogs – including L’art public à Montreal. À propos de quelques oeures extérieures (Montréal, Circa, 2007). Beaudet has seen her articles published in Canadian and foreign journals such as Le Devoir (Montreal daily newspaper), Esse (Montreal), Ceramics Art and Perception (Sheridan, Wyoming), Critique d’art (Rennes, France and C magazine (Toronto).

Pascale Beaudet – Translation / adaptation: Peggy Niloff

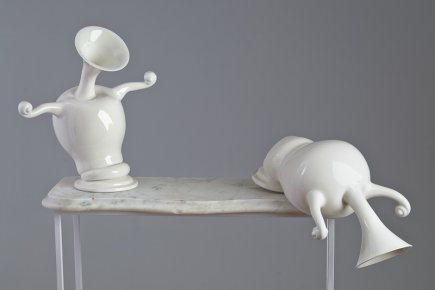

AT FRIST GLANCE, LAURENT CRASTE’S WORK MAY APPEAR TO BE ABOUT VIOLENCE & VANDALISM; HOWEVER, IN OUR INTERVIEW WITH THE FRENCH SCULPTOR HE MAKES IT CLEAR — IT’S MORE ABOUT MAKING STATEMENTS ABOUT HISTORY, LUXURY AND ULTIMATELY, VANITY.

Edited by Kirsten Matthew

DIRTY: WHERE DID YOU GROW UP?

LAURENT CRASTE: I was born and grew up in Orléans, France, a very old and historically rich city on the side of the Loire River. Even if it has been severely damaged by the American bombings during the WWII, it has still many ancient areas with medieval and renaissance buildings and churches. So, even if I didn’t come from a very wealthy family, I grew up surrounded with ornate façade, works of art and statues. A part of my family was living in Versailles, and we used to visit them frequently. To tell you how classical art was a normal element of my environment: when we wanted to have a little walk with the family dog, we used to go to the nearby park: the park of the Versailles castle! Landscaped by Le Nôtre, and full of sculptures and objet d’art….It was just natural to me, little child, to traipse around in the gardens of Louis XIV! This easy access to culture for anyone, because of its omnipresence, is a very fascinating aspect of Europe.

D: ARE THERE ANY OTHER ARTISTS IN YOUR FAMILY?

LC: I am the only artist in the entire family. My parents were state employees, other members of my family are lawyers, dentists or engineers. A very normal, middle-class family, not particularly interested or expert in art, especially contemporary art they were highly suspicious of! On the other hand, as almost everybody in France, they were very conscious and proud of the glorious artistic past of their country. So my familial background was naturally, if not actively, receptive to art.

D: ARE YOU WORKING ON ANYTHING AT THE MOMENT?

LC: Right now, I’m working on the shipping of two of my video installations to the Expo Shangaï 2010. It’s a lot of work and organization, and this management aspect of an artist’s carrier is not what I prefer to do, but it is essential. I’m also in the middle of an intensive teaching session at the college – this is a practice I feel very strongly about. I will return to my studio for some new creations later this spring, as I may participate to the Toronto International Art Fair next fall.

D: WHAT IS IT LIKE WORKING WITH PORCELAIN, COMPARED TO, LETS SAY CERAMIC?

LC: Your question is interesting, as it illustrates the very common confusion about ceramic and porcelain. In fact, porcelain is one of the three clay bodies – earthenware and stoneware are the two others – that are designated more generally as ceramic. So porcelain is ceramic, but indeed, porcelain is a particular kind of ceramic: purely white and vitrified after firing, it has always been surrounded by a special aura, because of its purity and translucence. The secret of its composition was kept during centuries by its discoverer – China, and it has been an object of fascination in the entire world and of an intense commercial traffic between the rich and mighty nobility of Europe and China’s imperial manufactures until the XVIII century, when its secret –kaolin – has finally been discovered in Germany in 1708. Then, European manufactures, run by and working for the nobility, developed in Europe, producing luxury objects of considerable values. For example, the Sèvres manufacture in France has been founded by Louis XV and his mistress, Mme de Pompadour, to provide the royal court with decorative objects in porcelain. This is because of these socio-economical and historical references that I use this special clay for my works. At the same time, this is a very delicate material that, compared to stoneware and earthenware, requires special cares to work with, especially meticulousness and precision, and these aspects suit my disposition perfectly.

D: WHAT ROLE DOES THE DECORATIVE OBJECT PLAY IN YOUR WORK?

LC: It is obviously fundamental in my practice, conceptually and physically. All my research centers on conceptual explorations of the multiple layers of meaning of decorative collectibles, in their sociological and historical dimensions, and also in their ideological and aesthetics ones. I consider the decorative object as a social indicator, a “sign bearer” (I quote here the French philosopher Abraham Moles). Considered alternately as instruments of political power, ideological vehicles, demonstrations of ostentatious luxury and economic power, or incarnations of emotions and experiences, the historical archetypes of decorative arts consummately provide me with useful material. I use them in different ways, through a process of violent deconstruction, or tactics of pictorial subversion, or as screens for video projections, depending with which conceptual aspect I want to deal. However, in any case in my approach, the decorative object ultimately embodies human vanity.

D: WHEN DID THE IDEA FIRST COME TO YOU TO EXPLORE CAPTURING THE ATTACKING & DESTROYING OF THE DECORATIVE OBJECT?

LC: I have always been fascinated by the phenomenon of vandalism, especially the ransacking phases that accompany revolutionary insurrections, when the works of art are destroyed because they incarnate an ideology, or symbolize a specific social class. This has been the case of course during the French Revolution, but also during the Chinese Cultural Revolution during the 70’s, when thousands of magnificent porcelains have been systematically destroyed, because they symbolized, in the eyes of Mao’s Red Guards, the bourgeois culture and the imperial power. This is after reading about this subject a few years ago, and after many years working as a more traditional ceramist, that I had the idea of exploring iconoclasm as a theme for creation. If I can intellectually understand the ideological motivations of such actions, I am horrified by the destruction of masterpieces, incarnation of human genius and beauty. And at the same time I am also totally fascinated by the destructive impulse, the violent nihilistic action. My works attempt to express this ambiguity and, paradoxically, I managed to transform an act of destruction in an act of creation.

D: BECAUSE IN SOME CASES, THE RESULTS ARE ORGANIC, A SURPRISE, DO YOU MAKE MULTIPLES?

LC: Because all my pieces are hand-thrown (I don’t use molds and the casting technique), I always work on a different, unique, object. But most of all, the action I subject them to is every time unique and the result is uncertain. So, it is absolutely impossible for me to reproduce a piece and make multiples. But what I can do is to act with the same kind of tool on the same type of object, and then the pieces will belong to the same conceptual «family», even if, formally, they will be inevitably different.

D: WHAT WILL YOU BE EXPLORING IN YOUR NEXT BODY OF WORK?

LC: I’m planning to work on large scale porcelain pieces. This is a technical challenge, but it will allow me to explore other intervention modes and to obtain new visual effects.

D: DO YOU WORK IN ANY OTHER MEDIUMS? WHAT ARE SOME OF YOUR OTHER INTERESTS?

LC: I use video projections in some of my works, using ceramic objects as screens for animated decorative motifs. It allows me to explore more poetic aspects of the decorative object. I do all the filming and the editing myself, and this is a technique I really enjoy to practice. I also would like to work with engraving techniques in order to explore the representation of objects.

D: WHO / WHAT MAKES YOU FEEL INSPIRED?

LC: All forms of classical, official or academic art inspire me – as I take much pleasure in corrupting it!

D: HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE YOUR SENSE OF HUMOR?

LC: Strangely, I did not initially intend to give a humorous aspect to my pieces, but they very often ended up looking funny. I now totally assume that. In fact, humor adds a derisory side to my pieces that I really like. I would say that this humor is truly tragi-comic.

D: IF YOU HAD NOT BEEN A VISUAL ARTIST, YOU PROBABLY WOULD HAVE CHOSEN TO BECOME:

LC: A pianist. I have been playing the piano since I was a child, and classical music is very close to my heart.

D: WHAT’S THE LAST GOOD BOOK YOU READ?

LC: I’ve just finished reading Gore Vidal’s historical novel «Julian», dealing with the life of the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate. A masterpiece.