IMAGES: KATE MacDOWELL Google Images

WEBSITE: KATE MacDOWELL

CONTACT: kate_macdowell@hotmail.com

GALLERIES:

BIO/CV:

I’ve lived and worked in many different environments and cultures that have influenced the way I perceive the world, and therefore my pieces. These experiences have ranged from teaching in urban high schools and producing websites in the high-tech corporate environment, to volunteering at a meditation retreat center in rural India a few hours outside of the fever pitch of Bombay. I’ve also collected visual imagery and ideas from my travels through Renaissance Italy, Classical and Minoan Greece, Nepal and Thailand.

Upon returning to the United States in 2004, after a year and a half working overseas, I began to study ceramics full-time at the ArtCenter in Carrboro, North Carolina and later at Portland Community College’s Cascade campus and the Oregon College of Art and Craft’s community education program. I have also studied flame-worked glass at the Penland School of Crafts in North Carolina, and participated in an artist residency at the Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts in Maine.

education

- 1995 Brown University, Providence, RI – Masters of the Arts of Teaching English

- 1994 Brown University, Providence, RI – BA in English and American Literature

awards/scholarships

- 2012 John Michael Kohler Arts/Industry Residency, Sheboygan, WI

- 2010 Professional Development Grant, RACC, Portland, OR

- 2009 Short-listed, Zelli Porcelain Award 2009, Zelli Porcelain, London, UK

- Best of Show, Feats of Clay 2009, Lincoln Arts & Culture Foundation, Lincoln, CA

- Winner, Ceramics: Hand-built/Molded, 2009 NICHE Awards, Philadelphia, PA

- 2008 Visionary Award of Excellence, CraftForms 2008, Wayne Art Center, Wayne, PA

- First Prize, Honorable Mention, Viewpoint: Ceramics 2008, Grossmont College, El Cajon, CA

- Best of Show, Clay? II, Kirkland Arts Center, Kirkland, WA

- 2007 Individual Merit Award, 2007 Craft Biennial, Oregon College of Art and Craft, Portland, OR

- 2nd place, Oregon Potters Association Ceramics Showcase, Portland, OR

- Bob & Peggy Culbertson Scholarship, Penland School of Crafts, Penland, NC

- Kiln God Residency, Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts, Newcastle, ME

solo exhibitions

- 2008After Eden, Beet Gallery, Portland, OR

- Window Project II, Blackfish Gallery, Portland, OR

selected group exhibitions

- 2012 Detailed Information, three person exhibit with Mindy Solomon gallery, St. Petersburg (May)

- Natural Macabre, group NCECA Concurrent Exhibition, Seattle Design Center (March)

- Earth Precipice, group NCECA Concurrent Exhibition, Seattle Design Center (March)

- SCOPE New York, group exhibit with Patrajdas Contemporary gallery, Philadelphia, PA

- 2011 SCOPE Miami, B-39, group exhibit with Patrajdas Contemporary gallery, Philadelphia, PA

- SCOPE Miami, C-21, group exhibit with Mindy Solomon gallery, St. Petersburg, FL

- Night Scented Stock, group exhibit with Marianne Boesky gallery, NYC, NY

- Shadowside, Part II, group exhibit with bo.lee gallery, London, UK

- Vernisage, group exhibit with Galerie Vanessa Quang, Paris, France

- Art Chicago, group exhibit with Patrajdas Contemporary gallery, Chicago, IL

- Florida Souvenirs, group exhibit with Mindy Solomon gallery, St. Petersburg, FL

- London Art Fair, group exhibit with bo.lee gallery, London, UK

- 2010 Find me a gift, group exhibit with Galerie Vanessa Quang, Paris, France

- Art London, group exhibit with bo.lee gallery, London, UK

- Animal Instinct, John Micheal Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI

- DIY: A Revolution in Handicrafts, Society for Contemporary Craft, Pittsburgh, PA

- BAM Biennial 2010: Clay Throwdown!, Bellevue Arts Museum, Bellevue, WA

- ArtHamptons, group exhibit with Mindy Solomon Gallery, Bridgehampton, NY

- Shadowside, bo.lee gallery, Bath, U.K.

- Art in the Kitchen, artKitchen and Gallery A, Art Amsterdam Fair, Netherlands

- NEXT Chicago, Patrajdas Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL

- Café Endlager, exhibition and technology museum, Stuttgart, Germany

- Bright and White, Mindy Solomon Gallery, St. Petersburg, FL

- Earth Matters, NCECA Invitational, Moore College of Art and Design, Philadelphia, PA

- CERAM-A-RAMA, Ceramics Research Center auction/exhibit, ASU Art Museum, Tempe, AZ

- Corporeal Manifestations, Mutter Museum, Philadelphia, PA

- 2009 Sitka Art Invitational, Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, World Forestry Center, Portland, OR

- Proverbial Porcelain, Zelli Porcelain, London, UK

- Art Fest of Clay and Fire, Sapporo Contemporary Museum, Sapporo, Japan

- CURIOSITIES, four person exhibition, Santa Fe Clay Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

- Feats of Clay 2009, Lincoln Arts and Culture Foundation, Lincoln, CA

- A Mixed Bag of Small Ceramic Wonders, Crossman Gallery, U of Wisconsin, Whitewater, WI

- 2009 NICHE Awards, Philadelphia Buyers Market of American Craft, Philadelphia, PA

- 2008 CraftForms 2008, Wayne Art Center, Wayne, PA

- Envisioning a Future, South Seattle Community College Gallery, Seattle, WA

- Sculpted Green, 2008 Bellevue Sculpture Exhibition, Bellevue City Hall, Bellevue, WA

- Viewpoint:Ceramics 2008, Hyde Art Gallery, Grossmont College, El Cajon, CA

- Clay? II, Kirkland Arts Center, Kirkland, WA

- 2007 Supernatural, PICA TBA:07, Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, OR

- 2007 Craft Biennial, Hoffman Gallery, Oregon College of Art and Craft, Portland, OR

- Oregon Potters Association Ceramics Showcase, Oregon Convention Center, Portland, OR

- The Figure: transcribing the human form, Western Oregon University, Monmouth, OR

selected publications

- 2011 Rooms Magazine (UK), “Kate MacDowell…”, by Adan Jerreat-Poole, pp. 12-19, issue #7

- SKULL STYLE: Skulls in Contemporary Art and Design (New York), by Farameh Media LLC

- Tomorrow’s World, cd and single cover art designed by Tom Hingston for Erasure album

- Kult Magazine (Singapore), “Animals” issue

- Bioephemera, “Kate MacDowell: Bloodless Bodies”, by Jessica Palmer, Sept 7

- Doppelganger: Images of the Human Being (Berlin), by Gestalten: exploring visual culture

- American Craft, “Craft’s New Consciousness”, by Savannah Schroll Guz, Feb/Mar, pp. 26-27

- 2010 Ceramics Art and Perception, “Corporeal Manifestations”, by Colette Copeland, Dec #82

- Dark Inspiration: grotesque illustrations, art and design (Hong Kong), viction:ary, pp. 46-55

- American Style, “Kate MacDowell”, 2010 Emerging Artists, issue 74, Nov

- Ms. Use (Israel), Eco Sex, vol. 2, summer

- BANG Art (Italy), Speciale Animali, “Amabilichimere”, by Rosa Maria Albino, pp. 74-75, #7

- Quotation: Worldwide Creative Journal (Japan), by Daisuke Nishimura, p. 51, no. 8, summer

- Western Humanities Review, cover art and multiple photo illustrations, Vol. LXV, no. 2

- Creative Review Magazine (U.K.), “Hi-Res” pp. 20-21, June

- Bear Deluxe Magazine, The Creative Nonfiction Issue, “Independent Art”, #30, p. 3

- 2010 NCECA Invitational Earth Matters Catalog, essays by Nichole Burisch and Glen Brown

- Hi-Fructose Magazine, “Cross-sectioning Ghosts with Kate MacDowell”, Jen Pappas, Vol 15

- Spraygraphic (blog), “Spraygraphic Interview with Artist Kate MacDowell”

- O.K Periodicals (Netherlands), Vol. 4, “Curiosities”, p. 80

- Calle20 Magazine (Spain), “Escultures de Sueños”, Luisa Bernal, pp.18-23, No. 46

- New York Times Sun. Magazine, “Is There an Ecological Unconscious? “, photo illustrations

- notcot, streetanatomy, formfiftyfive, abduzeedo, paulbaines, treehugger, juxtapoz and others

- 2009 Lobster and Canary (blog), “6 + 1 Interview: Kate D. MacDowell”, by Daniel A. Rabuzzi

- Ceramics Monthly, “Curiosities”, Upfronts section, September, p. 18

- The: Santa Fe’s Monthly Magazine for the Arts, “Curiosities”, by Marin Sardy, August, p. 56

- 500 Ceramic Sculptures, Juror: Glen R. Brown, Editor Suzanne Tourtillott, Lark Books

- 2008 425 Magazine, “Sustainable Sculptures – Seeing Green in Bellevue”, Jenny Lynn Zappala

teaching experience

- 2010 Transforming the Natural World, summer workshop, Santa Fe Clay, Santa Fe, NM

ARTIST STATEMENT

|

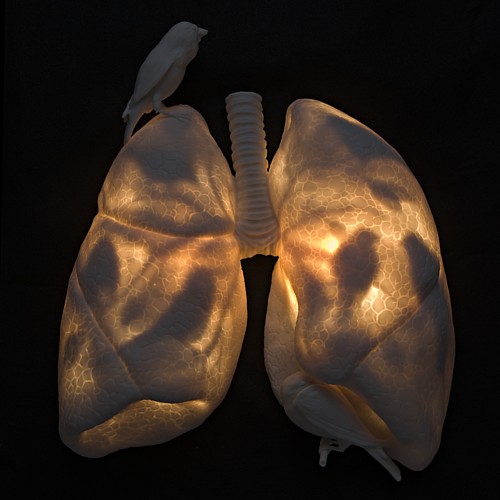

| 6+ 1 Interview: Kate D. MacDowell

Kate D. MacDowell hand builds porcelain into figures (birds, rabbits, human hands, nests) that one is certain will move. But they won’t, will they? Truncated, stripped back as if on the anatomist’s table to reveal transposed organs and misplaced skeletons, these creatures are gorgeous grotesques, chimerae, small fragile renderings of death. For more images and her resume, see Kate’s website. Here’s what Kate told the lobster and the canary: “I fell in love with clay as soon as I first started working with it about four years ago. Prior to that I taught English to high school students and produced websites for hi-tech companies. Although I had just finished a year and half working at a meditation retreat center in rural India, it wasn’t until stopping off in Italy for several weeks on the way home that it fully hit me that making artwork was not an indulgence but served a vital need. I’ve been lucky to be able to work in the studio full-time since then, and continue to collect visual imagery and ideas from travelling to Classical Greece, Nepal and Thailand, where I almost never take pictures, but just absorb”. Thanks Kate, and now for your questions. Question 1: You pass finally through the hedgerows, after walking the smuggler’s trace between hawthorn, rowan and bramble, scrambling over the thorn-brakes and out of blind sumps, where the windle sang mockingly and iridescent flies flocked ’round your face. At last you reach the meadow, in sunlight, and hear the sound of horns off distant hillsides. A huge oak stands alone in the middle of the meadow. At its roots is a bronze box, whose key hangs from a nail driven into the tree. What do you find when you open the box? How do you share your discovery with the rest of us? Kate answers: I’m inclined to take this question literally as my in-law’s live at the end of a Viking/Smuggler’s trace on the Isle of Man. What I have found on or around that trace in the past include: a rooting hedgehog, a jogger-attacking billy goat, a tiny shrine with a Buddha and coins, the British farm odor of burning tires and fresh cow dung, and blooming gorse. In the bronze box I find some 10-shilling notes and a bottle of whiskey (galore!) found and hidden away after the wreck of the SS Politician. What do you mean share? Question 2: I love the C.S. Lewis quote that heads the artist’s statement on your website: “We do not want merely to see beauty…we want…to be united with the beauty we see…to become part of it.” I think often of Lewis’s use of the German concept Sehnsucht, impossible to translate fully into English, but connoting a sense of longing for places we have never seen (and that may or may not even exist), of loss, nostalgia, separation. Does Sehnsucht play a role in your creative process, and, if so, what triggers the yearning, where are you trying to take us? Kate: Yes, I think so. I experienced this very strongly reading “Tintern Abbey” in college (and bursting into tears unexpectedly in my concrete bunker of a dorm in a noisy East Coast city) and soon after I left the US for Scotland to follow that feeling. But what I was looking for seemed always out of reach, even in the apparent wilderness of a hike in the highlands I would find myself longing to experience the primeval past. The quality of our lives, the very way we perceive ourselves and find happiness is completely different when we are living closer to the natural world. Anyone who walks into a grocery store after a three-day backpacking trip feels the jolt. I’m trying to remind myself, and others, of feelings many of us had as children hunkered down on our bellies with the grass growing tall above our heads, pondering the world of the ants and inch-worms, or caught up in the tragedy of a dead sparrow on the sidewalk. Question 3: Your work is self-described as in part a response to (here I paraphrase) human encroachment on and abuse of the rest of the natural world. Your work speaks deeply to me in this respect: each piece strikes a warning note, embodies a mute but eloquent admonition. I see your work as standing in (among other things) the vanitas andmemento mori tradition exemplified by Dutch painters in the 17th-century, reminding viewers of our prideful folly and inescapable mortality. For instance, you “dissect” birds and animals to reveal a skeleton within…and go beyond the tradition by making the skeleton human within a non-human corpse. To what extent do you reference the Old Masters, old techniques, old tropes– and why might you do so? Kate: I do definitely reference old tropes and specific works. My art education has been largely experiential (wandering through museums in Rome, Paris, London, and Athens) rather than academic, except for a great art history survey course in college taught by an expert on Dutch painters of the 17th century….so I respond more to what I’ve seen in person and what has fascinated me. So far that has included a lot of work of the Italian Baroque, especially Bernini and Caravaggio. I think right now I am approaching my work more as a kitsch artist might (as defined by Odd Nerdrum – not in the ironic sense), than a contemporary artist – in part because the themes you mention. The evocation of emotions such as intimate loss and grand tragedy, and the utilization of parables and myths fit more comfortably for me into pre-modern frameworks. I also study natural forms closely and attempt to sculpt them realistically by hand which for the most part has been out of fashion for the last century. I also really like contemporary environmental / land art a la Andy Goldsworthy so my approach may change. Question 4: As you note, porcelain is strong but fragile– the threat of shattering is ever present. In one of your signature pieces, Daphne, the nymph and tree are in fact shattered. Reminds me of the Jewish concept of tikkun olam, the imperative to repair a splintered world, glue back the shards of divinity. Tell us more about your choice of porcelain as your medium. Kate: Fitting– I first fell in love with it because I was carrying an elaborate finished and dry porcelain piece into the studio, and it bumped into a table and shattered into thousands of pieces on the concrete floor. I was briefly in shock and didn’t have anything better to do for several hours, so started picking up the tiny pieces and wetting the edges with a brush to stick them back to each other. You can’t usually do this with dried clay, but with porcelain you can. I reassembled the piece after a day or so, and fired it with few ill effects. Porcelain still develops cracks more than any other clay body, but it also seems to offer more opportunities to patch and move on at various stages. Esthetically, I first started working with porcelain because of its’ translucent qualities, when lit from within I could evoke the effect of an ultrasound or x-ray. I could also reference marble sculpture (classical and baroque), and draw the viewer’s eye to the form rather the surface colors of the piece. A pure white piece also speaks to me of ghosts or negative space–it suggests something missing from the world. Question 5: Your earlier works seem more explicitly narrative (for instance, Tyger, Tyger), while your current style is more lyrical. Also, you no longer paint the porcelain. Tell us about the evolution in your technique and form-making, and where you may be heading next. Kate: My earlier body of work was a visual response to figurative language, in particular, an attempt to render into three dimensional space the imagery evoked by certain poems that had stuck with me over the years (“To his Coy Mistress” and “From the Republic of Conscience”, for example) . I almost always started with a title before envisioning the piece, and I still am more comfortable with words than images. My sketchbook is full of sentences describing ideas for pieces rather than drawings. The technique change (from using color and a narrative approach) followed the change in thematic focus to environmental issues. As I move forward I want to engage much more directly with the natural environment, either by placing and photographing groupings of work in wilderness settings (the artist Lotte Glob who lives in Scotland does some interesting things, or by doing larger multi-piece installations that create more of an immersive environment (for example, a ghost rainforest: a small room in which you are surrounded by trees, leaf mold, birds, and insects all rendered life-size from white porcelain). I’m not sure when this work will get made because of practical and financial considerations, but that’s where I feel the pull. Question 6: Your figures, both human and animal, are exquisitely rendered. What is your process? How do you structure– or not– your periods of observation and modeling? Do you sketch regularly, and then refer to your sketches? Do you use maquettes, make bozetti, use CAD-CAM or other digital visualization tools? Kate: I really need to sketch out variations and make tiny maquettes more often in order to explore bringing more torsion and movement into my work (as Beth Cavener Stichner does – http://www.followtheblackrabbit.com/index_main.htm). I do sometimes make models but I usually have a very detailed mental photograph of the finished piece before I begin so I skip that step a lot. The only modern technology I rely heavily on is the Google image search function — I type in anything: “pigeon foot”, “dead mouse”, “frog deformity” and instantly pull up photographs from various angles. I have a dusty laptop cycling images and a pushpin covered wall of color prints whenever I’m working. I’m always looking as closely at photographic source images as possible. I work from life when I can, though a trout on a melting pile of ice in your studio is only bearable for a day or two. I rarely use or make molds although I do pick up texture by rolling clay over tiny leaves, for example. I usually build a piece solid and then hollow everything out to 1/4″ thickness. The structural implications of putting together delicate and complicated natural forms are sometimes intriguing, sometimes maddening. Lobster & Canary says: Your turn, Kate. Ask Lobster & Canary a question! Kate: What do you recommend for the best books to listen to on mp3, disk, or tape while carving away in my basement studio for hours at a time? I love good character-driven fantasy and sci-fi (Bujold’sVorkosigan series and Song of Ice and Fire are my top choices so far primarily for cumulative length, quality, and ability to keep me sucked into the story and working through the night when necessary). But I have also had some great listens all over the map from children’s books, to 18th and 19th century classics, to historical nonfiction. Natural Macabre, Roxanne Jackson, Shay Church, Kate MacDowell. Work that explores images of death and transformation and values macabre sensibilities. As death beckons rebirth, the real becomes surreal, the natural world a fantastic one. Organized by Roxanne Jackson. r. Roxanne Jackson , The Precious Object

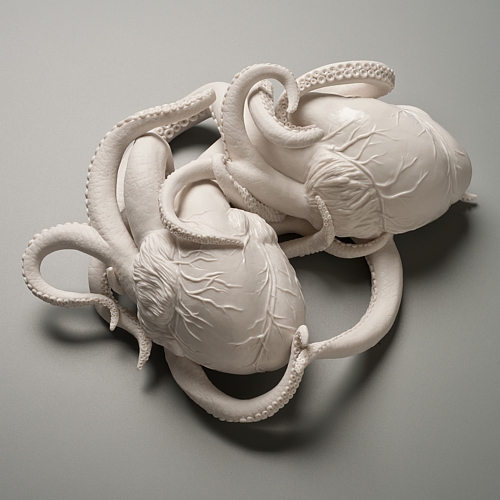

Kate Macdowell Porcelain: Explorations of Humans and Nature Kate Macdowell creates stunning works out of porcelain. Kate’s work is aesthetically beautiful, but also has a lot of depth, as her pieces explore the interaction of humanity and nature. These quirky works are cute and creepy at the same time. Kate loves to show links between humans and our connection to nature, despite our society’s attempts to remain as distant as possible from the natural world. Kate is a master at composition, and is able to create wonderful scenes from what would otherwise appear to be a random jumble. Every shard is carefully placed to create something that is beautiful from any angle. Kate’s attempts to show the link between humanity and nature can be seen easily in these pieces, in which a human skeletal system is revealed to be inside each animal. Both intricate and a bit disturbing, Kate’s pieces have a refreshing depth. Kate Macdowell isn’t without a sense of humor, and her pieces show the human / nature link in visually stunning (and fun) ways. Rabbits with gas masks and humans with multiple eyes might seem to be just fun, but Kate is actually making a very strong comment on pollution and the environment. Few of Kate’s pieces reveal man and nature as inextricably linked, as these. With roots growing directly out of human limbs, and entire ecosystems teeming within the smooth porcelain, it’s hard not to see us as very much a part of the natural world. Kate MacDowell: Porcelain Artifacts sculptor Kate MacDowell of Portland, Oregon, USA, depicts the fragility of nature and humanity through a romanticized connection between the human body and the environment through porcelain figures. the entirety of her work draws upon historical figures and events, art history, and Greek mythology. the interaction between the modern human and the environment is evident as a motivation for the artist in the rendering of each figure. MacDowell’s works are initially formed by hand from a solid piece of porcelain with the depth and layering of each construction epitomizing her unique interaction with this medium. the smaller figures within each piece are made individually as the artist develops a tangibly intimate interaction with each structure. her choice of porcelain has an ethereal effect on her finished pieces– each work is rendered with exquisite detail, the delicate quality as ultimate strength of the porcelain is magnified by her wonderfully unsettling combination of elements of nature on or in the human form. MacDowell’s collection has an impression of biological accuracy, resulting in an artifact or specimen like treatment of each piece. ‘quiet as a mouse’ (below) is currently on display in the exhibit ‘night scented stock’ at the Marianne Boesky gallery in New York city from now until the 22nd of October.

http://scienceblogs.com/bioephemera/2011/09/07/kate-macdowell-bloodless-butch/Kate MacDowell: bloodless bodies Posted by Jessica Palmer on September 7, 2011 Kate MacDowell sculpts partially dissected frogs, decaying bodies with exposed skeletons, and viscera invaded by tentacles or ants. It’s the imagery of nightmares, death metal music videos, or that tunnel scene in the original Willy Wonka (not a speck of light is showing, so the danger must be growing. . . ). But her medium – minimalist, translucent white porcelain – renders her viscerally disturbing subject matter graceful, even elegant. Some of her pieces, like Sparrow, below, play off the porcelain’s resemblance to delicate bleached bone. In others, the permanence of the porcelain generates tension with the ephemeral forms it depicts – like insects, leaves, and flowers. MacDowell’s work explores how the “romantic ideal of union with the natural world conflicts with our contemporary impact on the environment.” In Sparrow, the chimera of a human skeleton inside a broken bird-body has an apparently clear message: what we do to our world, we do to ourselves. We are biologically and ecologically interrelated. But in other pieces, like the installation Quiet as a Mouse, the message is not so clear. MacDowell explains that this sculpture is based on images of the Vacanti mouse which became an online visual meme and sparked heated discussion about genetic engineering, animal testing and various related ideas, often based on a misunderstanding of the image that was further distorted by the online game of telephone (for example, human genetic material was not used in the experiment, the “ear” was a synthetic construct). Though the ear-mouse is at first glance a real-world embodiment of MacDowell’s human-animal chimeras, that’s only the (incorrect) interpretation the public readily placed on it. Yes, it was a mouse with a genetically compromised immune system, but it was not genetically engineered to grow a human ear, nor were human cells used in the ear. Rather, it carried the illusion of a human ear – a proof of concept, a biomedical tool intended to eventually transform our own bodies. Thinking about how the ear-mouse was misunderstood/understood by the public prompts us to consider where our own first reactions to MacDowell’s other artworks are justified, or if we need to look again. Kate MacDowell graciously agreed to answer a few questions about how she uses anatomical and biological imagery in her work; her answers (and more of her work) are below the fold. BioE: I’d love to share with my readers how you first became inspired to incorporate such a broad swath of anatomical imagery into your work. I see from your resume that you are not a biologist by training; how did you develop your eye for anatomical accuracy – dissections, study from specimens, etc.? K MacD: Most of it is from observation and having sketched from life since I was a teenager. That made the transition into sculpting natural forms much easier. I have taken a figure sculpting class that focused on the human body – skeletal systems and muscle groups, and what I generally do when sculpting an animal is to go online to google images and collect source pictures of the forms I’m going to be sculpting, from as many angles as possible. I also do a little reading about the environmental issue or case study I’m exploring in order to understand it more deeply. K MacD: I make sure to find scientific drawings as well as both professional and snapshot photographs. Diagrams of skeletal systems are especially good for figuring out proportions, because they are the framework that I can then build the muscle/fat/fur around. I really haven’t done any dissections or taken post-high school biology classes. Occasionally I will have an actual animal skull to study, or a trout I can buy at the supermarket or something, and plants are fairly easy to substitute for one another (when taking impressions of leaf veins, for example). I also have a lot of plastic miniature animal toys that help with basic proportions in 3d. BioE: To what extent do you think your chosen medium mitigates (or dilutes) the instinctive distaste many people have for cadavers/exposed viscera, and how do you use that in your work? K MacD: I purposely like to use the conflict caused by the pairing of beauty with the macabre or grotesque in my work to evoke an (often conflicted) emotional response so that viewers will spend more time with the piece. By making the pieces out of delicate white porcelain, with a classical/baroque style more often seen in marble sculpture it does invite people closer to spend more time studying the forms and textures without being instinctively turned off by lots of slippery red meat. Often they miss the darker messages until this closer inspection. I like that there is sometimes a bit of a time lag in responses to my work, then lot’s of “ewws” and some smiles and laughs. Kate’s Quiet as a Mouse installation will be on view in the “Night Blooming Stock” group exhibition at Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York, opening Sept. 14th. You can also see her work on the cover of Erasure’s new album “Tomorrow’s World”, designed by Tom Hingston, as well as on their single covers – Hingston colorized her white sculptures to interesting effect (here’s a fan-made video juxtaposing the single cover with the original Solastalgia).

|